Table of Contents

ToggleThe national campaign, initiated with the “Year of Return, Ghana 2019” and extended through the decade-long “Beyond the Return” initiative, has successfully catalyzed significant interest and investment from the Global African family, particularly within the real estate sector [1, 2, 3]. The objective of this analysis is to provide a definitive guide to leveraging these policies for secure, long-term relocation and asset ownership in Ghana, focusing critically on the interplay between legal status, constitutional property rights, and mitigating investment risk.

While the national initiatives have fostered a welcoming environment and resulted in streamlined administrative support, the perception of “simplified property acquisition” must be understood as administrative and legal reinforcement, not an elimination of necessary due diligence [2, 4]. The most profound simplification mechanism is the enactment of the Land Act 2020 (Act 1036), which directly addresses historical tenure insecurity and systemic challenges, backed by dedicated governmental support infrastructure, notably the Ghana Investment Promotion Centre (GIPC) Diaspora Desk and the Office of Diaspora Affairs [5, 6, 7].

The central legal imperative governing property investment in Ghana is the distinction between a citizen and a non-citizen. This status difference directly dictates the maximum permissible tenure and, consequently, the long-term value and security of the asset. Non-citizens are constitutionally restricted to a 50-year leasehold, whereas Ghanaian citizens are entitled to a significantly more secure 99-year leasehold [8, 9]. Furthermore, tax differentials in rental income heavily favor residents. Therefore, maximizing tenure security, minimizing long-term operational costs, and optimizing returns necessitate the strategic pursuit of full Ghanaian Citizenship or formal long-term residency.

Primary recommendations derived from this analysis emphasize immediate engagement of specialized land law counsel, mandatory verification of title and ownership through the Lands Commission, and the strategic prioritization of full Ghanaian Citizenship to unlock superior land tenure rights and achieve the most favorable tax treatment, specifically the lower resident withholding tax rate on rental income [10, 11].

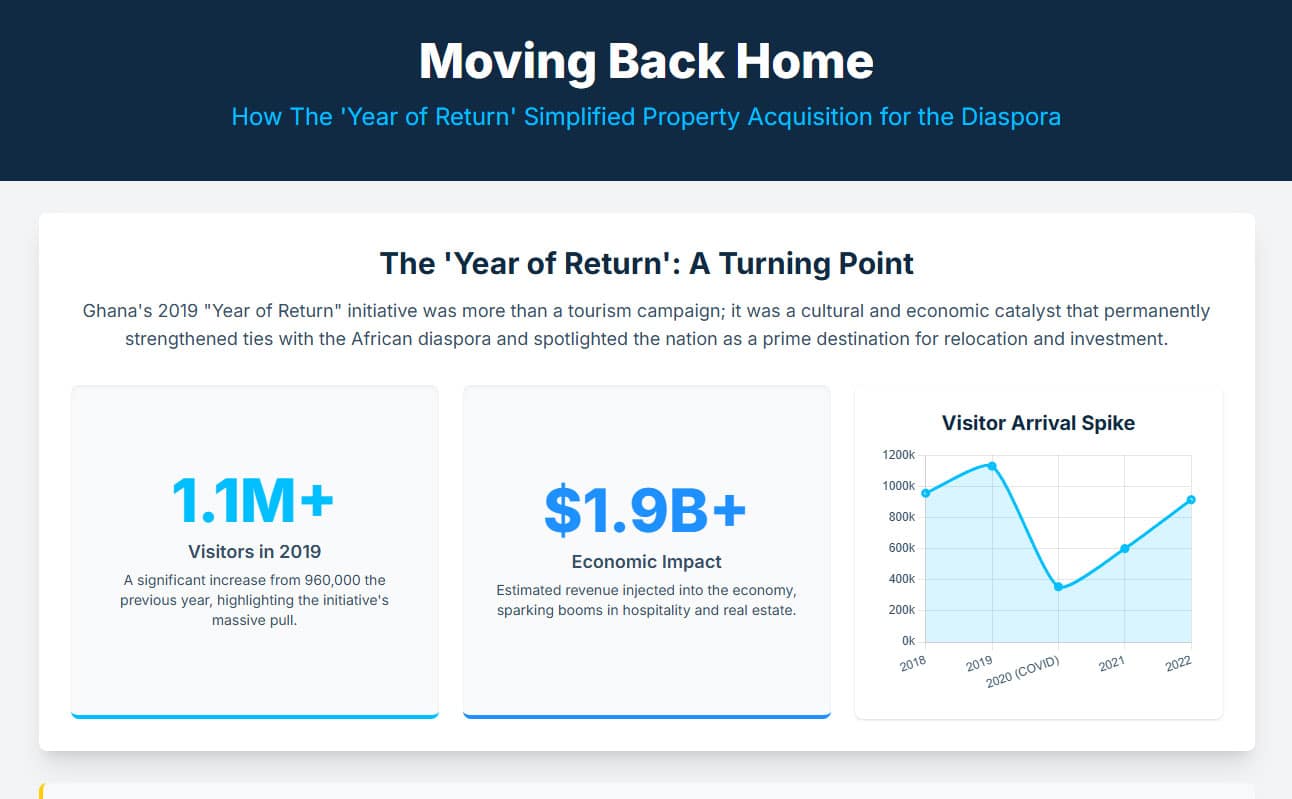

The Ghanaian government’s focused strategy to engage the diaspora began with a highly successful cultural and symbolic campaign. The Year of Return, Ghana 2019 commemorated the 400th Anniversary of the arrival of the first recorded enslaved Africans in Jamestown, Virginia, marking a spiritual and birth-right journey for the Global African family. The campaign was designed to celebrate the resilience of the African identity and position Ghana as a key destination for African Americans and the broader Diaspora [1, 3].

This initiative laid the groundwork for the current phase, Beyond the Return (2020-2030). Operating under the theme, “A Decade of African Renaissance,” the follow-up project explicitly shifts focus from symbolic homecoming to long-term connections, economic integration, and investment. Key objectives include creating memorable experiences through cultural events and tourism, but crucially, establishing sustained economic relationships [1]. The overall policy objective is aligned with the President’s vision of ‘Ghana Beyond Aid,’ utilizing tourism and diaspora investment as leading indicators for national economic growth and development [3].

The high level of enthusiasm generated by the initial campaign, particularly the surge in real estate interest in areas like Accra, Cape Coast, and Kumasi [2], necessitated a formal, institutional response to manage the influx of capital and mitigate potential investment friction. The government formalized support structures to provide official, trustworthy channels for investors.

The Ghana Investment Promotion Centre (GIPC) Diaspora Investment Desk is mandated under the GIPC Act, 2013 (ACT 865), to encourage, facilitate, and promote investments in Ghana by providing a transparent, predictable, and facilitating environment [7]. GIPC actively runs investment roadshows and links diaspora capital to national development initiatives [12]. Similarly, the Diaspora Affairs Ghana organization offers specialized investment support, providing financial guidance and trusted pathways for diasporans. This office is critical for furnishing regulatory guidance, investment due diligence, and facilitating partnerships with verified, on-the-ground entities, which is crucial for navigating the inherent complexity of the local market [6].

The institutional push toward formalization is a mechanism to manage risk perception among international investors. Policy promises, such as “simplified property acquisition processes” [2] and goals to “remove obstacles to the acquisition of land” [4], are tangible efforts to address known challenges like land disputes and corruption. Furthermore, Ghana’s strong incentive to protect diaspora investment is measurable; the nation is a major recipient of international remittances, with figures ranging from USD 3.54 billion to USD 4.98 billion annually, representing over 10 percent of the national GDP [4, 10]. The government’s proactive steps to modernize land law, such as the Land Act 2020, are directly intended to market Ghana as a secure and reliable investment destination, countering negative international narratives regarding land tenure risk. This institutional strengthening represents a shift from a purely symbolic gesture to a strategic, economically integrated effort.

For any substantial, long-term property investment in Ghana, the applicant’s legal status is the single most important factor. Ghana’s constitutional framework imposes specific restrictions based on whether an individual is classified as a citizen or a non-citizen, thereby dictating the maximum permissible lease term for land tenure. This classification profoundly affects the long-term investment cycle, value, and inheritable security of the acquired property [5, 8].

Foreign nationals who wish to pursue a specific purpose, such as study, business, employment, or missionary work, must acquire a standard residence permit [13]. This status is inherently purpose-tied, meaning the holder cannot pursue any work, business, or profession except as specified in the permit [13]. Documentary requirements for these permits are extensive, including company registration documents, tax clearance certificates, employment contracts, curriculum vitae, a police report from the applicant’s home country, copies of professional certificates, and a medical examination conducted at the Ghana Immigration Service (GIS) Headquarters [13]. Holders of this status are legally classified as non-citizens and are subject to the 50-year property lease limitation.

The Right of Abode is a form of residence status specifically conferred upon individuals of African descent in the diaspora [14, 15]. This status offers significant logistical advantages for returnees, granting the right to live and work in Ghana indefinitely, the ability to enter Ghana without a visa, and the right to work as a self-employed individual or employee without needing an additional work permit [14, 16].

However, the application process for the Right of Abode is rigorous and designed to ensure economic commitment and integration. Requirements include:

A careful review of this status reveals a critical legal limitation. While the Right of Abode confers indefinite stay and professional freedom, addressing the major operational hurdles for returnees, it remains an Immigration Status granted by the Minister and approved by the President [15]. The holder is still, legally, a non-citizen. As the 50-year lease restriction is explicitly tied to non-citizen status [8, 9], the Right of Abode holder remains subject to this constitutional tenure limit. The status simplifies the act of living and working but does not maximize property investment security. Furthermore, the extensive requirements for this status, demanding attestation by highly respected local professionals and verifiable evidence of economic embedding, ensure that the applicant’s capital is tracked, legitimized, and contributing formally to the national tax base, aligning bureaucratic control with the state’s economic objectives.

Acquiring Ghanaian Citizenship is the only way for diaspora investors to access the superior 99-year leasehold tenure and resident tax advantages.

Citizenship by Descent is the most direct route for those with documented Ghanaian parentage. Applicants must provide evidence of their descent, current passports of their Ghanaian parent(s), evidence of their other country’s citizenship, and a full birth certificate [17, 18].

Citizenship by Registration or Naturalization typically requires the applicant to have resided in the country for at least five years [19]. The process involves purchasing and submitting Application Form (Form 3) at the Ministry of the Interior, along with a copy of the current or Indefinite Residence Permit page. Additional requirements include necessary documents for naturalization, such as a passport bio-data page [19]. For spouses of Ghanaian citizens, a consent letter from the spouse and a copy of the marriage certificate are also required [19].

The following table summarizes the legal distinctions that directly impact investment decisions:

Table I. Legal Status and Property Rights Comparison

| Legal Status | Maximum Land Tenure Lease | Visa/Work Requirement | Property Transfer Tax Liability (Initial) | Rental Income Tax (Withholding) |

| Ghanaian Citizen | 99 Years (Renewable) [8, 9] | No requirement (Inherent Right) | Standard Resident Rates | 8% Withholding Tax (Resident Rate) [10] |

| Foreign National (Standard Permit) | 50 Years (Renewable) [8, 9] | Yes (Purpose-tied) [13] | 5% Property Transfer Tax [10] | 15% Withholding Tax [10] |

| Diaspora (Right of Abode) | Likely 50 Years* | No Visa/Work Permit required [16] | 5% Property Transfer Tax [10] | 15% Withholding Tax (Non-Resident Rate) [10] |

Advisory Note: The Right of Abode status, while granting indefinite residency, does not confer full constitutional citizenship property rights and is legally expected to fall under the 50-year restriction for non-citizens, subjecting the holder to the same leasehold and tax limitations as other foreign nationals.

Ghana operates under a complex land tenure system where land rights are derived from a dual legal structure: statutory and customary law. Freehold ownership, which grants absolute, indefinite control over property, is generally not available for land acquisition by the public [5]. In practice, true freehold is rare, primarily limited to Ghanaian citizens acquiring state land through presidential grants [5, 20]. The vast majority of commercial, agricultural, and residential land is leased from clan leaders, communities, or the government [20].

The prevalent system is Leasehold ownership, which provides exclusive use rights for a defined, but temporary, period [21]. The duration of the lease is strictly governed by the nationality of the lessee:

It is crucial to differentiate between the land and the physical structure. Foreigners are permitted to fully own built properties, such as houses, apartments, and condominiums, but the underlying land is always subject to the leasehold system [9]. Leasehold properties are considered secure investments, provided they are properly documented, transferable, and renewable [5]. Contrary to common misconceptions regarding seizure, the lease can typically be renewed at expiration. Expert legal assistance is necessary to ensure the actual indenture includes a clause specifying automatic renewal at a reasonable cost [8].

The difference in tenure length creates a substantial operational distinction. Leasehold owners are required to pay ground rent, whereas freehold owners bear complete responsibility for all property-related costs [5]. More significantly for foreign investors, the constitutional restriction limiting non-citizens to 50 years (half the duration granted to a citizen) means the investment requires renewal negotiations and associated transactional expenses twice as frequently as a citizen-held asset, effectively shortening the predictable amortization period.

The Land Act 2020 (Act 1036) represents the most direct and substantial legislative effort by the government to enhance tenure security and streamline acquisition for investors, directly addressing known systemic issues such as lack of transparency and corruption [22]. This Act serves as the tangible mechanism of policy simplification promised under the ‘Beyond the Return’ initiative.

These legislative actions function collectively as an anti-corruption and investor confidence-building package. By targeting the three main vectors of insecurity—physical violence, documentation fraud, and data ambiguity—the Land Act provides a robust legal foundation intended to replace uncertainty with predictability for diaspora investors.

Acquisition of property in Ghana requires meticulous due diligence, particularly when navigating land ownership derived from customary authorities, where legal and communal claims can sometimes conflict. While the political climate is welcoming, the complexities of land tenure mandate strict adherence to formal processes.

To mitigate the inherent risks associated with title conflicts and ensure legal defensibility, the following six steps are mandatory for any serious diaspora investor:

The reliance on both legal registration and physical demarcation acknowledges that historical legal processes have sometimes proven insufficient due to enforcement weaknesses and poor record-keeping [22]. The government’s explicit criminalization of land guards provides the necessary state enforcement power to solidify the tenure established through these combined legal and physical acts.

Despite legislative improvements, investors must be cognizant of residual systemic challenges, including the potential for conflicting claims arising from the inclusion of customary lands in development projects intended for returnees [23]. These issues stem from a historical lack of updated land data, limited transparency, and difficulty accessing reliable land information [22].

To manage potential conflicts efficiently, the Land Act 2020 introduced a crucial procedural safeguard. It mandates that parties involved in land disputes must first exhaust all procedures under the Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Act, 2010 (Act 798), before proceeding to litigation in traditional courts [24]. The Lands Commission is actively training its staff in negotiation, mediation, and conflict resolution to handle these mandated ADR processes internally [24]. This legal requirement to use ADR creates a specialized, accelerated resolution pipeline, strategically de-risking the investment by offering a faster and more efficient mechanism for conflict resolution compared to the traditional courts, which are often “choked with too many land dispute cases” [24]. This procedural reform fulfills the policy goal of removing obstacles to land acquisition by drastically reducing the timeline and uncertainty associated with resolving title conflicts.

Financial planning for property acquisition requires a detailed understanding of the tax regime, particularly the distinctions imposed upon resident citizens versus foreign non-residents. The total initial transaction costs for property acquisition typically range between 5 percent and 8 percent of the property value [10].

The initial acquisition involves several mandatory levies and professional fees:

The most significant recurring financial differentiator for diaspora investors is the tax treatment of passive income, specifically rental income. This tax structure is explicitly designed to incentivize formal, long-term residency.

The continuous 7 percent differential in annual rental income tax creates a compelling, recurring financial disadvantage for the non-resident investor. This substantial disparity is interpreted as a deliberate government strategy: rather than merely attracting transient capital, the tax policy compels the long-term, passive investor to formalize their residency or citizenship status in Ghana. By doing so, the investor aligns their financial optimization with the ‘Beyond the Return’ goal of permanent, tax-paying reconnection and economic integration.

The Ghanaian real estate market demonstrates stability, with property appreciation averaging 5-7 percent annually [10]. This stability, coupled with high remittance inflows, supports a positive long-term investment outlook [4]. Furthermore, Ghana maintains a liberal capital repatriation policy, which permits the complete repatriation of capital and profits through authorized dealer banks. This policy is vital for mitigating liquidity risk and assuring investors of the ability to retrieve their return on investment [10].

Table II. Estimated Transactional and Operating Costs for Diaspora Investors

| Cost Component | Estimated Rate/Range (of Property Value) | Frequency | Differential Based on Status | Source |

| Property Transfer Tax | 5% | One-time (Initial Purchase) | Foreign buyers pay 5% | [10] |

| Stamp Duty | 0.25% – 1% | One-time (Initial Purchase) | Uniformly applied | [5, 25] |

| Legal/Professional Fees | 1% – 2% | One-time (Initial Purchase) | Uniformly applied | [5] |

| Annual Property Rates | 0.5% – 3% (of Assessed Value) | Annually | Varies by municipality/property type | [10, 26] |

| Rental Income Withholding Tax | 15% (Non-resident) vs. 8% (Resident) | Recurring (Annual Income) | 7% recurring financial penalty for non-residents | [10] |

The policy initiatives stemming from the ‘Year of Return’ have not simply simplified property acquisition; they have fundamentally restructured the legal and administrative environment to attract and protect diaspora investment, notably through the Land Act 2020. However, the path to secure, optimized ownership is differentiated by legal status.